Racers sit in four chairs as they race to connect their headsets to the live feed.

Racers sitting in front of the race track, a C-124 Globemaster II.

Photos by Ethan Charles | Greene County News

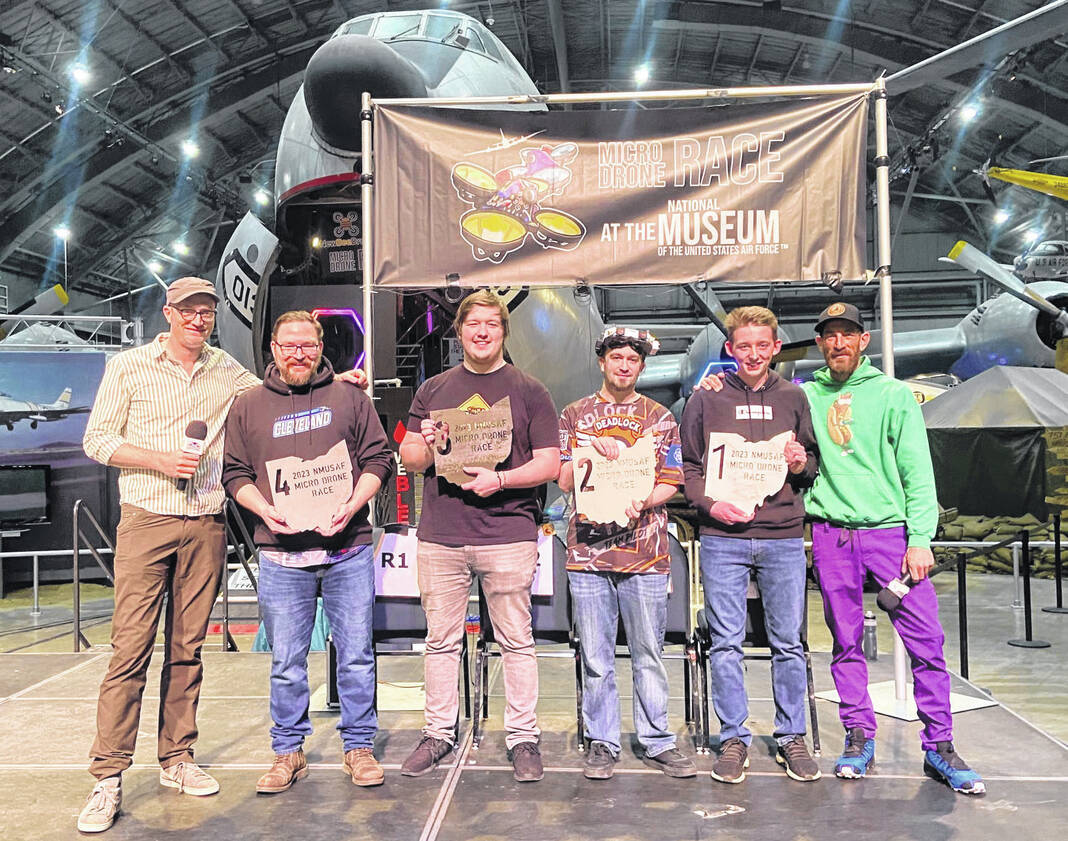

Jesse Perkins (left) and Kele Stanley (right) congratulate the top four winners in the sport class.

FAIRBORN — A brand new sport is in the making as the National Museum of the United States Air Force hosted the fourth annual micro drone race this past weekend.

From Feb. 24-26, the second hanger at the museum was occupied by 64 drone racers flying through and around a C-124 Globemaster II, the racetrack for the event. The first two days consisted of qualifying rounds run in sets of four, with the final tournaments taking place on Sunday.

The racers themselves came from all across the country and of all ages to compete at this tournament that, according to Jesse Perkins, founder of micro drone races (called Tiny Whoops), is one of the largest in the country.

The drones, reaching no more than a couple of inches in length, are difficult to pick out as they race through the track, and impossible to follow along the whole time. So how do these racers do it?

The answer? Tiny cameras mounted on each drone that feed directly into the specialized headsets each racer is wearing, giving a first-person view (FPV) of what the drones are seeing. The live footage was also projected onto two other large-screen feeds for the audience to keep up with what the fliers were seeing. This allowed for not only an extremely competitive scene for the racers but an energized crowd following along in the action.

“You see some very competitive players,” said Daniel Driscol, one of the event organizers for the race. According to Driscol, the tiny drones are cheaper and lower the barrier of entry compared to the more robust drones in the official Drone Racing League, or DRL. Because of the cheaper price, it’s the easiest drone racing league to get into.

Curtis Carll was one of the racers for the event and had a different opinion.

“That’s debatable,” he said regarding the ease of access. According to Carll, the smaller drone’s fragility meant a small mistake could render a drone obsolete, costing the racer more in replacements than a larger drone that may not break so easily.

Jesse Perkins came up with Tiny Whoop and the micro-drones that were used at this event. He, along with event organizer Kele Stanley co-announced in the museum and live online on the Tiny Whoop YouTube page. Perkins, who came up with the idea for Tiny Whooop in late 2015, has big plans for the future of the sport that has only gotten bigger.

“My goal is to make a big race like this into an international series,” said Perkins.

As the biggest drone race the museum has seen so far, that may very well be in the sports’ near future. For now, Perkins is happy with the community he’s helped create and people he’s met along the way.

“Pretty much everybody that comes into the drone scene one way or another ends up making great friends,” he said.

Stanley had similar sentiments about the Tiny Whoop community.

“My favorite part about this event in particular is just how many people it brings together,” said Stanley. “I like the camaraderie of all of the guys that are flying, we all have a similar mindset.”

Not only is there a great community and intense competition, but drone racing has practical applications as well.

Nicole Tefft is the mother of Tristan “TDog” Tefft, a flier who is greatly considered one of the fastest micro drone racers on earth. According to Tefft, her son got into drone racing just a few years ago, and because of his newfound talent has decided to go to college for aerospace engineering and aviation.

The tournament Sunday was split into two classes: The sports class and the pro class. Winners of the sports class received an Ohio-shaped plaque and cheers from the crowd, while pro class winners walked away with similar plaques as well as a cash prize reaching up to $1,200, a check Tefft’s son ended up taking home.

The cash prizes, totaling $3,000 altogether, were donated by “We Bleed FPV,” the event’s biggest longtime sponsor.

Winning wasn’t the only way to walk come with a prize, however. Stanley was adamant about giving back to the racers so invested in the sport, and both Friday and Saturday Stanley held giveaways for the racers nearly once every half-hour.

“They pay 50 bucks to race,” he said. “I want to make sure that not only do they get the experience, they get the value out of it by getting something now.”

The camaraderie and competition between racers is clear, and as drone racing becomes more popular and technologically advanced, we can expect to see more races in the near future.

“I’m sure that we’ll be back next year,” said Stanley.